Portrait miniatures

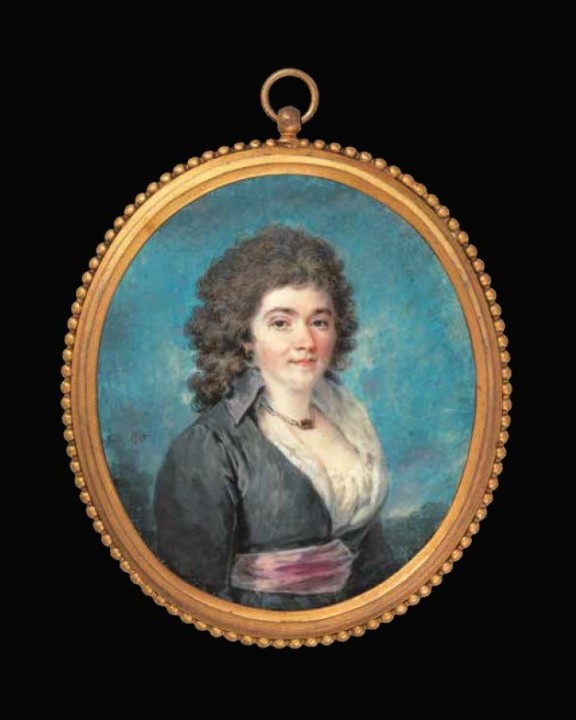

Portrait miniatures are, as the name implies, hand-painted portraits of small and extremely small size, ranging from less than a centimetre to around twenty to twenty-five centimetres in height, or sometimes more.

From the middle of the sixteenth century up to the invention and spread of photography in the middle of the nineteenth century, they fulfilled their specific purpose: to allow people to carry with them a likeness of a loved one as true to life as possible, or also to provide an idea of the outward appearance of a person that one had not yet met but might well like to meet (if the appearance, as rendered, was in fact appealing). Thus up until the nineteenth century, long before the era of internet dating, the exchange of portrait miniatures was the only opportunity for prospective brides and grooms, who had often never seen each other in a time of generally arranged marriages, to discover whether they actually found each other attractive (which was, of course, ultimately only of secondary importance).

When people dear to one another, especially couples and families, were forced to be apart – a circumstance all too familiar these days – the portrait miniature served as a stand-in for the absent person, like today’s photo in a wallet or selfie on an iPhone. For this reason such miniatures played a particularly significant role in times of crisis or war. Thus one is struck by the fact that the miniature collection at the Museum Liaunig contains an especially large number of portraits from the politically troubled period of the English Civil War during the time of Oliver Cromwell in the middle of the seventeenth century, as well as numerous portraits from the years of the French Revolution and the subsequent Napoleonic Wars between 1790 and 1815.

From a collection of by now over 300 miniatures, a representative selection of more than 120 pieces from the beginning of the seventeenth to the end of the nineteenth century are being displayed in this second exhibition, and the 100 most beautiful examples have been documented scientifically in a new catalogue of nearly 400 pages published in 2020.

Miniatures are generally painted with very light-sensitive watercolours and are thus displayed to the public only in very few museums. Interested persons are generally only permitted to see individual pieces upon request in the study rooms, as is the case in the Louvre and the Albertina. Thanks to our state-of-the-art technology, the Museum Liaunig is currently one of the very few museums in the world, and the only one in Austria, to grant the interested public access to such a large quantity of significant miniatures.

The first display cases of the exhibition contain seventeenth-century English works from the reign of the Stuarts. These watercolour miniatures, up to four centuries old, are presented to visitors only under very muted light conditions, to protect these rare treasures for future generations of visitors as well. Merely five centimetres high, a portrait of a young woman with a clearly visible wart is the earliest and also most valuable piece in the entire hall of miniatures. It was painted by the renowned Isaac Oliver (ca. 1565–1617), court painter to the virgin Queen Elizabeth I and her successor King James I, son of the unfortunate Mary Stuart. One of the Liaunig family’s favourite artists was Samuel Cooper (1608/1609–1672), court miniaturist to King Charles I, who was to share the cruel fate of his grandmother under the axe of the executioner. Samuel Cooper worked diligently, without any hesitancy or remorse, for the man responsible for the death of his former employer: Oliver Cromwell. After Cromwell’s reign of terror, when Charles’s son ascended the throne, Cooper was immediately named royal court painter once again. From the numerous Cooper miniatures in the Liaunig collection, six can be viewed in the current exhibition.

The Liaunig collection is particularly rich in attractive eighteenth-century miniatures from Italy, France, Great Britain, Russia and Scandinavia. An extra display case is dedicated to the German Heinrich Friedrich Füger (1751–1818), court miniaturist under the Emperors Joseph II and Leopold II. But Austria’s most successful miniature painter of all time was undoubtedly Moritz Michael Daffinger (1790–1849). All Austrians of the pre-Euro generation are familiar with Daffinger, as a copper engraving based on a miniature self-portrait of his, belonging to the Museum Liaunig, served as the model for the last 20-schilling banknote. His seven particularly beautiful works, now on display for the first time, are among the highlights of the Museum Liaunig’s miniature collection. The exhibition concludes, also chronologically, with miniatures and watercolours from Daffinger’s pupils, successors and contemporaries, including two rare miniature portraits by the famous Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller.

Dr. Bodo Hofstetter

(Curator)

Collection "Portrait miniatures II“

Curator: Bodo Hofstetter

28 April to 31 October 2024 ∙ Wednesday to Sunday 10 am to 6 pm

Museum Liaunig ∙ 9155 Neuhaus/Suha 41 ∙ Austria ∙

+43 4356 211 15

office@museumliaunig.at ∙ www.museumliaunig.at